Whānau Māori Voice

Understanding what is important to whānau Māori in our Ngāi Tahu Takiwā helps us to achieve the best health outcomes, support improved health sector performance and shape the design and delivery of health services and public health interventions to have maximum benefit for Māori.

A new section on our website provides a summary of what we already know about the needs and aspirations of whānau Māori in our Takiwā, and identifies areas where there are gaps in our knowledge.

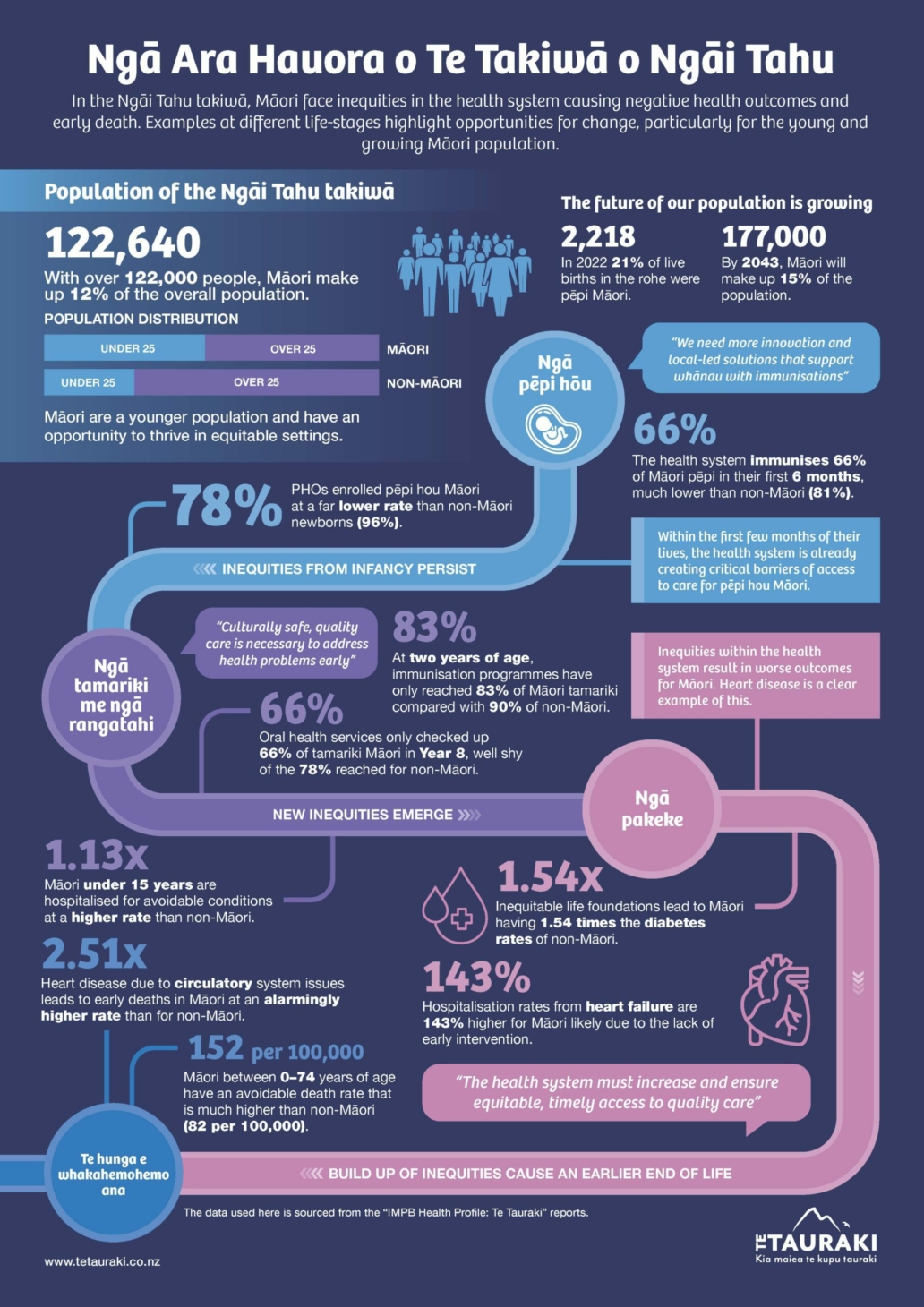

Te Tauraki Health Profile

Te Tauraki Health Profile Infographic

Whānau Māori Aspirations

This section looks at what we know about whānau Māori hopes and aspirations when it comes to health and wellbeing and the wider determinants of health.

Overall we can see:

01

Whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā see hauora as a holistic concept.

02

Being well requires a connection to our Ngāi Tahutanga and Māori culture.

03

Mātauranga Māori must be respected and valued as part of a commitment to Māori health.

04

The use of Te Reo Māori is also important, with 11.7% of Māori in the Takiwā regularly speaking Te Reo Māori in the home.

05

Whānau Māori aspire to be in control of the decisions that affect their lives

06

Having local Māori decision-making in health services and funding supports whānau Māori aspirations and trust and confidence in the health system.

Connection to Te Ao Māori is important

Many Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā see connection to and involvement in Māori culture as at least somewhat important (59.8%). Only 14.3% of Māori in our Takiwā see it as not at all important. Spirituality is seen as very important by nearly 20% of Māori in the Takiwā.

Importance of being involved in Māori culture, Māori aged 15 years and over, Te Tauraki and Aotearoa, 2018

| Te Tauraki | Aotearoa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| Very important | 11.7 | (9.9, 13.5) | 22.1 | (21.2, 23.1) |

| Quite important | 21.0 | (18.5, 23.5) | 23.2 | (22.1, 24.3) |

| Somewhat | 27.1 | (24.0, 30.0) | 25.8 | (24.7, 26.9) |

| A little important | 26.0 | (22.5, 29.4) | 18.3 | (17.1, 19.5) |

| Not important at all | 14.3 | (11.6, 16.9) | 10.6 | (9.7, 11.6) |

Importance of spirituality, Māori aged 15 years and over, Te Tauraki and Aotearoa, 2018

| Te Tauraki | Aotearoa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| Very important | 19.8 | (17.1, 22.5) | 30.7 | (29.5, 31.9) |

| Quite important | 17.5 | (14.9, 20.1) | 18.0 | (16.9, 19.0) |

| Somewhat | 17.2 | (14.6, 19.8) | 16.8 | (15.9, 17.8) |

| A little important | 17.2 | (14.9, 19.5) | 15.3 | (14.3, 16.2) |

| Not important at all | 28.4 | (25.5, 31.2) | 19.2 | (18.1, 20.4) |

In 2018, almost all Māori aged 15 years and over in our Takiwā had been to a marae (89.9%), and of those around 30% had been in the last 12 months.

Of those who had been to a marae and who knew their ancestral marae, around 70% reported that they would like to go more often.

In the Takiwā, around 11.7% of Māori aged 15 years and over used Te Reo Māori regularly in the home. This is below the rate of Te Reo Māori use in the home by Māori nationally (18.4%).

In 2018, around 6% of Māori aged 15 years and over in the Takiwā had taken part in traditional healing or mirimiri in the past 12 months, compared with 12.3% of Māori nationally.

Māori involvement in decision-making is essential

“We need data sovereignty for Te Waipounamu. The data belongs to us and will allow us to hold the power and support whānau to make informed decisions.”

– South Island participant, Hui Whakaoranga, 2021

Whānau Māori in our Takiwā are seeking greater voice in decision-making at the local level [Ngā Wānanga Pae Ora 2023].

The Ministry of Health reports that one of its key findings from engagement in Te Waipounamu as part of its Hui Whakaoranga in 2021 was that Māori seek more control over decisions that affect our communities.

This includes decisions over:

- Health sector investments

- Commissioning of health services

- The services whānau Māori access, without becoming more reliant on health services

- Māori-led services

- The use of data and Māori data sovereignty principles.

Wellbeing is about more than health services

“The policy environment needs to change. We are living in a country that disenfranchises and perpetuates poverty.”

– South Island participant, Hui Whakaoranga, 2021

Whānau Māori within our Takiwā have broad understandings of hauora that includes:

- Making nutritious food more affordable (Hui Whakaoranga 2021) and supporting food sovereignty, for example through māra kai (Takiwā Poutini 2023)

- Ensuring people are paid liveable wages (Hui Whakaoranga 2021)

- Providing healthy homes for whānau (Hui Whakaoranga 2021)

- Seamless connection across health and other government sectors (Takiwā Poutini 2023)

“We need collaboration between all the organisations supporting Māori, health, social, etc. Join up all the care.”

– Takiwā Poutini community engagement, 2023

Mātauranga Māori must be respected and valued

Whānau Māori in our Takiwā have emphasised the need to see mātauranga (Māori ways of knowing and being) in action, for example, through greater support for rongoā, widespread use of Te Reo Māori, and Māori-led and Iwi-driven approaches. [Ngā Wānanga Pae Ora 2023].

Whānau Māori have also spoken for the need for permanent spaces for Māori practices, including for wānanga (forums, workshops, learning environments) and mātauranga. (Takiwā Poutini 2023)

A growing body of Kaupapa Māori Research also emphasises the importance of Mātauranga Māori (see for example Rewiti et al (2023)).

Attention needs to be given to the needs and aspirations of tāngata whaikaha Māori

According to the last New Zealand disability prevalence survey, 26% of Māori (compared with 24% of the general population) self-report disability.

However, due to a lack of clear definitions around disability that are meaningful for tāngata whaikaha Māori (Māori with lived experience of disability), existing data must be interpreted with caution.

There is a growing body of tāngata whaikaha Māori-led research. This includes findings of a series of semi-structured interviews that included a small number of tāngata whaikaha Māori who live in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā or whakapapa to Ngāi Tahu (Ingham et al, 2022). This study highlighted four areas of multidimensional nature and impacts of inequities for tāngata whaikaha Māori”

- Inequitable access to the determinants of health and wellbeing

- Inequitable access to and through health and disability care

- Differential quality of health and disability care received, and

- The need for Indigenous, Māori-led, solutions.

Demographics and health status

This section looks at data and other evidence related to the demographics and health status of whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā.

Overall we can see:

01

The Māori population in the Takiwā is growing, particularly in the 65 years and over age group

02

Life expectancy for Māori in the Takiwā is 82.4 years for females and 78 years for males

03

There is a gap in life expectancy between Māori and non-Māori, non-Māori female life expectancy nearly 2 years longer than for Māori females, non-Māori male life expectancy nearly 3 years longer than for Māori males

04

Many whānau Māori in the Takiwā report being in good health

05

The leading cause of death for Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā between 2014 and 2018 was Ischaemic heart disease.

Population and age

Around 122,640 Māori live in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā (as of 2023). The population is very young, with 48% of the Māori population in the Takiwā aged under 25 years, compared to only 27% of the non-Māori population).

The following table shows the number of Māori and non-Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā by age band.

Population estimates by age group and ethnicity, Te Tauraki 2023

| Age Group | Māori | Non-Māori | Total IMPB Number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Age distribution | % of IMPB | Number | Age distribution | % of IMPB | ||

| 01 - 4 | 35,660 | 29% | 12% | 143,005 | 15% | 178,665 | |

| 15 - 24 | 22,830 | 19% | 12% | 115,050 | 12% | 137,880 | |

| 25 - 44 | 32,635 | 27% | 12% | 255,630 | 27% | 288,265 | |

| 45 - 65 | 21,945 | 18% | 12% | 244,670 | 26% | 266,615 | |

| 65+ | 6,985 | 6% | 12% | 183,600 | 20% | 190,585 | |

| Total | 122,640 | 100% | 12% | 939,810 | 100% | 1,062,450 | |

Over the next two decades, the Māori population within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā is projected to grow to around 176,940. This population is also expected to be older with around 11% of the Māori population aged over 65 years in 2043, compared to 6% in 2023.

The following table shows the population projections for Māori and non-Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā in five-year increments between 2023 and 2043. This information is also broken down into age bands.

Population protections for Te Tauraki, 2023 to 2043

| Year | Māori | Non-Māori | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | % of IMPB | 0-14 years | 15-64 years | 65+ years | Residents | % of IMPB | 0-14 years | 15-64 years | 65+ years | |

| 2023 | 122,640 | 12% | 29% | 63% | 6% | 939,810 | 88% | 15% | 65% | 20% |

| 2028 | 136,450 | 12% | 27% | 63% | 8% | 962,430 | 88% | 14% | 64% | 22% |

| 2033 | 150,260 | 13% | 27% | 63% | 9% | 981,590 | 87% | 13% | 64% | 23% |

| 2038 | 164,930 | 14% | 26% | 62% | 10% | 995,700 | 86% | 13% | 63% | 25% |

| 2043 | 176,940 | 15% | 25% | 63% | 11% | 1,003,670 | 85% | 12% | 63% | 25% |

Births

In 2022, there were 2,218 Māori babies born in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā, making up about one fifth of all babies born in the region. More information on birth rates by district is available in Te Tauraki Māori Health Profile Volume Two.

Births for Te Tauraki, 2022

| Indicator | Māori | non-Māori | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of all live births | Number | |

| Births | 2,218 | 20.7 | 8,489 |

Source: National Maternity Collection, Ministry of Health: Maternity Qlik.

Life expectancy

Life expectancy at birth for Māori born in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā is 82.4 years for females and 78 years for males. As in other parts of the country, non-Māori have longer life expectancy (the life expectancy for non-Māori females is nearly 2 years longer than for Māori females, and life expectancy for non-Māori males is nearly 3 years longer than for Māori males). However, there is a variation between regions with South Canterbury showing the largest life expectancy gap at over 4 years shorter for non-Māori males. This life expectancy gap by ethnicity is less pronounced than it is nationally (where Māori life expectancy is around seven years shorter than non-Māori).

Life expectancy at birth for Te Tauraki for Māori and non-Māori, by gender (2018 to 2022)

| Sex | Māori | non-Māori | Difference in years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | (95% credible interval) | Years | (95% credible interval) | ||

| Female | 82.4 | (81.4, 83.3) | 84.2 | (84.0, 84.4) | -1.8 |

| Male | 78.0 | (77.3, 78.8) | 80.7 | (80.6, 80.9) | -2.7 |

Source: Mortality data sourced from Ministry of Health. Mortality Collection. https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/national-collections-and-surveys/collections/mortality-collection. Population denominator data from Statistics New Zealand, Population estimates (2022 update). Analysed by Michael Walsh, Equity, Scientific and Technical Team, Equity Directorate, Service Improvement and Innovation, Te Whatu Ora; October 2023.

Within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā, there are variations to life expectancy for Māori across the former DHB regions:

- In West Coast DHB life expectancy at birth is 79.4 years for Māori females (3 years shorter than non-Māori females) and 75.8 years for Māori males (2.3 years shorter than non-Māori males)

- In Canterbury DHB life expectancy for Māori was 82 years for females (2.3 years shorter than non-Māori females) and 77.7 years for Māori males (3.2 years shorter than non-Māori males).

- In South Canterbury DHB life expectancy for Māori was 82.4 for Māori (0.5 years shorter for Māori females, which is the smallest life expectancy gap across the Takiwā), and the life expectancy for Māori males was 75.7 (4.1 years shorter than for non-Māori males, the largest life expectancy gap across the Takiwā)

- In Southern DHB life expectancy for Māori was of 82.8 years for Māori females (1.3 years shorter than non-Māori females) and 79 years for Māori males (1.6 years shorter than non-Māori).

The leading causes of death contributing to the life expectancy gap for Māori in Te Waipounamu (used as a proxy for the Takiwā) are coronary disease (which contributes a gap of 0.5 years) and land transport injuries (0.3 years).

Self-assessed health

In 2018, 86.1% of Māori in the Takiwā reported their own health as good, very good, or excellent.

A total of 13.9% of Māori in the Takiwā reported their health status as fair or poor (compared with 17.7% of Māori nationally) in the Te Kupenga survey.

Mortality

The leading causes of death for Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā between 2014 and 2018 were:

- Ischaemic heart disease,

- Lung cancer,

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),

- Suicide, and

- Cerebrovascular disease.

This varies slightly to the leading causes of death for Māori nationally, where suicide does not feature in the five leading causes, but diabetes does. The pattern is also different for non-Māori in the Takiwā (for non-Māori the leading causes of death over the same period were heart disease, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, and lung cancer).

More detail on leading causes of death for Māori and by former-DHB region is available in Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume One. (December 2023)

When looking at the age-standardised death rate in Te Tauraki by ethnicity, the rate is 1.5 times higher for Māori compared with non-Māori. This equates to around 134 Māori females and 179 Māori males dying each year in the Takiwā.

Potentially avoidable deaths

Potentially avoidable deaths that could have been avoided by high-quality healthcare, prevented through public health intervention, or both.

The leading causes of potentially avoidable for Māori aged 0-74 years in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā are:

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Lung cancer

- Suicide

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and

- Motor vehicle accidents.

This varies slightly from the leading causes of potentially avoidable deaths for Māori nationally (where motor vehicle accidents to not feature, but diabetes does).

More detail on leading causes for potentially avoidable deaths is available in the Iwi-Maori Partnership Board Health Profile.

Whānau Māori health and well-being

This section shares findings relevant to whānau Māori health and wellbeing.

Māori health and wellbeing status is about more than the absence of disease in individuals. Importantly, Māori models of health are holistic and often emphasise the importance whānau Māori thriving as a collective.

Overall, from the information and data we have been able to access, we observe:

01

Many Ngāi Tahu whānau Māori surveyed (79%) report being in good overall health

02

Around three quarters of Māori report that their whānau is doing well or better, and around a quarter report that their whānau is not doing so well

03

While most Māori in the Takiwā had whānau of ten people or less (57%), around a quarter (23.6%) had between 11 and 20 members

Whānau Māori generally feel positive about their health and wellbeing

In 2018/19 Ngāi Tahu in collaboration with Research First developed a whānau Māori survey to better understand Ngāi Tahu whānau Māori members. Key insights of the report showed:

- Many whānau Māori reported being in good overall health and wellbeing (79%)

- Many whānau Māori feel positive about their physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing (around 70%)

- Older whānau members and those with more financial security provided higher ratings on all wellbeing measures in the survey

- Many respondents were able to identify areas of their wellbeing that needed support (80%); of these support with te taha tīnana / physical support and cultural well-being were the most common identified.

Many, but not all, whānau Māori are doing well

On a scale from 0 (doing extremely badly) and 10 (doing extremely well) many Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā report that their whānau was at 7 or greater (meaning that their whānau is doing well). However, just under a quarter (23.8%) reported that their whānau was not doing so well.

This is consistent with the findings of He Tohu Ora (which was developed between Ngāi Tahu and Te Pūtahitanga o Te Waipounamu to represent indicators that reflect a Māori view of wellbeing). As part of He Tohu Ora, many respondents in the South Island rated their whānau Māori wellbeing as 7 or above (out of 10).

The following table gives whānau Māori well-being as reported in the 2018 Te Kupenga survey for Māori aged 15 years and over in Te Tauraki and across Aotearoa.

Whānau Māori wellbeing reported by Māori aged 15 years and over, Te Tauraki and Aotearoa, 2018

| How the whānau is doing | Te Tauraki | Aotearoa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| (10 out of 10) | 10.4 | (8.4, 12.4) | 12.9 | (12.1, 13.7) |

| (9 out of 10) | 16.7 | (14.2, 19.1) | 12.8 | (11.9, 13.6) |

| (8 out of 10) | 25.1 | (22.5, 27.8) | 24.4 | (23.3, 25.6) |

| (7 out of 10) | 24.1 | (21.3, 26.9) | 23.5 | (22.5, 24.6) |

| (0-6 out of 10) | 23.8 | (21.2, 26.3) | 26.4 | (25.2, 27.6) |

Source: Te Kupenga 2018, Statistics New Zealand customised report.

The Te Kupenga Māori Social Survey also asked Māori about who made up their whānau. While most Māori in the Takiwā had whānau of ten people or less (57%), around a quarter (23.6%) had between 11 and 20 members. In the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā just under a quarter of Māori (22.5%) also included ‘close friends or others’ in their thinking about whānau.

Most Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā reported that it was easy or very easy to get support in times of need.

Health and well-being services

This section shares findings relevant to health and wellbeing services in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā. In this section, we are aware of the limitations of the data we have access to. We note that a second volume of the Te Tauraki health profile is to be included, and that this will look at additional indicators in priority areas such as cancer, long-term conditions, first 1,000 days for pēpī and whānau, and mental health.

Overall, from the information and data we have been able to access, we observe:

01

Many whānau Māori are satisfied or very satisfied with the health and wellbeing services they access

02

There remain several challenges for the health system as it strives to deliver culturally safe care for all whānau Māori, including tāngata whaikaha Māori (Māori with lived experience of disability)

03

The primary health care system has not enrolled 14.8% of the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā compared to 1.4% of non-Māori.

Many Whānau Māori are satisfied with the health and disability services they access

In 2018/19 Ngāi Tahu in collaboration with Research First developed a whānau Māori survey to better understand Ngāi Tahu whānau members. Key insights of the report relevant to health services showed:

- Many respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with the health and well-being services they accessed (between 72% and 97% of respondents)

- Many respondents reported having not had trouble accessing health and well-being services (71%).

- Those who did have difficulty accessing services were mostly likely to identify difficulties associated with their cultural and physical wellbeing

- Many whānau Māori reported that their main access to health information was through a health practitioner (78%), and 70% said they searched for information online. Almost half of respondents also reported going to whānau Māori for health information.

Access to high quality primary health care is an ongoing issue

- In the former West Coast DHB region, the primary health care system had not enrolled 8.8% of Māori

- In the former Canterbury DHB region, the primary health care system had not enrolled 12.9% of Māori

- In the former South Canterbury DHB region, the primary health care system had not enrolled 17.8% of Māori

- In the former Southern DHB region, the primary health care system had not enrolled 17.8% of Māori.

Barriers to accessing primary health care

“The system changes need to include adequate, appropriate, cultural supervision; acknowledge the different roles in the system and examine how power plays out in clinical settings.”

– South Island participant, Hui Whakaoranga, 2021

Local reports from within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā shine a light on the barriers to accessing primary health care for whānau Māori. These include:

- Barriers around patient co-payments, consultation times, pharmacy open hours, and access to oral health care, including for tāngata whaikaha Māori (Māori with lived experience of disability) (Takiwā Poutini, 2023 and Christchurch Clinical Network, 2022)

- The selective closure of general practice books, especially for high-needs patients (Christchurch Clinical Network, 2022)

- Frustration at a lack of progress and cultural considerations for Māori well-being, including addressing racism (Christchurch Clinical Network, 2022)

- Impacts of discrimination and other barriers for some population groups (including Māori and Pasifika whānau, culturally and linguistically diverse groups, the LGBTQIA+ community, and rural populations (Christchurch Clinical Network, 2022).

Access to maternity care

Access to high quality antenatal care early in a pregnancy is an important part of ensuring the best possible outcomes for māmā and pēpi.

Between 2018 and 2022, just over three quarters of Māori women (75.9%) within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were enrolled with a Lead Maternity Carer (for example a midwife or private obstetrician) within their first trimester of pregnancy (that is within the first 14 weeks of pregnancy). In comparison, 85.1% of non-Māori women were enrolled with a Lead Maternity Carer in their first trimester.

Life expectancy at birth for Te Tauraki for Māori and non-Māori, by gender (2018 to 2022)

| Indicator | Māori | non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av. no. per year | % of live births (95% CI) | Av. no. per year | % of live births (95% CI) | ||

| First trimester registration | 1,591 | 75.9 (72.2, 79.7) | 7,358 | 85.1 (83.2, 87.1) | 0.89 (0.87, 0.91) |

Source: National Maternity Collection, Ministry of Health: Maternity Qlik.

Note: First trimester is defined as conception up until 14 weeks of pregnancy.

There are several studies looking at pregnancy and birthing experiences for Māori. This includes the impact of māmā experiencing multiple stressful life events during pregnancy and in the first years of their child’s life, which is more common amongst Māori (Paine et al, 2023). There is also evidence that Wāhine Māori who give birth by emergency caesarean delivery value being included in the medical decision-making process around giving birth, even in emergency situations, and having whānau support, including those who can advocate for them. The ability for Māori whānau to have access to and observe tikanga/traditional practices is also seen as very important (Lawrie et al, 2024). The best possible outcomes for mama and pēpi can be bolstered through holistic models of care that include the immersion of hapū (pregnant) māmā in learning raranga (weaving) and result in strengthen social networks (Te Huia et al, 2023).

Primary and community care for pēpi Māori

Primary care enrolment

One indicator of how well primary care and maternity systems are working is how early newborn babies are enrolled with a primary health care provider after their birth. In 2022, with the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā, 77.6% of pēpi Māori were enrolled in with a primary care provider by the time they were three months old. In the same year, non-Māori babies were more likely to be enrolled in primary health care at the same age (96.4%).

Enrolment with primary care by three months of age, 2022

| Indicator | Period | Māori | non-Māori | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Newborns enrolled with a Primary Health Organisation (PHO) by three months old | Sep to Dec 2022 | 427 | 77.6 | 2,055 | 96.4 |

Source: Well Child/Tamariki Ora Indicators, Ministry of Health, March 2023.

Notes: Numerator source: PHO Enrolments. Denominator source: National Immunisation Register.

Oral health

Oral health care is free in New Zealand for tamariki and rangatahi up to 18 years of age, and all children should be enrolled with local community oral health as soon as possible after birth. In the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā, 81.8% of Māori children aged 0 to 4 years were enrolled with community oral health services compared with 93.4% of non-Māori children.

Looking at attendance at oral health services, only 56.3% of eligible Māori five-year-olds attended community oral health services in 2022 (and non-Māori five-year-olds attended at very similar rates). However, in that same year, tamariki Māori in year 8 (around 11 or 12 years old) were less likely than non-Māori students to attend community oral health services (66.0% for Māori compared with 77.9% for non-Māori).

| Age group | Māori | non-Māori | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. eligible | No. examined | % examined | No. eligible | No. examined | % examined | |

| Age 5 | 2,140 | 1,205 | 56.3 | 9,080 | 5,189 | 57.1 |

| Year 8 | 2,330 | 1,538 | 66.0 | 10,360 | 8,075 | 77.9 |

Source: For number eligible: StatsNZ population projection for 2022. For number examined: Community Oral Health Service, Ministry of Health.

Of the tamariki Māori who were seen by community oral health services in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā in 2022, nearly half had decayed teeth and for both Māori five-year-olds and Māori Year 8 students the rate of decayed teeth was higher than for their non-Māori counterparts.

For more information on child oral health in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā, including a break down by former DHB region, please see Te Tauraki Māori Health Profile Volume Two [insert link].

Access to appropriate outpatient care is lower for Māori than non-Māori

Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā are much more likely to have a missed first specialist appointment than non-Māori. In 2023, for example:

- 8.5% of first specialist medical appointments for Māori were missed, compared to 3.8% of appointments for non-Māori,

- 14% of first surgical appointments for Māori were missed, compared to 5.5% for non-Māori.

- The level of missed appointments varied with age and was highest for Māori aged 30 to 39 years (with 18.7% of appointments missed for Māori, compared to 8.2% for non-Māori).

Access to appropriate outpatient and hospital care has decreased across the country over the past four years. By November 2023, the number of people waiting more than 4 months for a first specialist assessment was five times the number waiting in February 2020. For example, in November 2023, nearly a quarter of Māori said they couldn’t get health care because wait times were too long. For more information on the national picture of access to health care, you can refer to Window on Quality 2024 on the website of Te Tahu Hauora (the Health Quality and Safety Commission).

Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā have higher rates of hospitalisation than non-Māori

Between 2020 and 2023 there were an average of 20,762 hospital admissions each year, 1.1 times the rate of hospitalisation for non-Māori. Māori females had the highest rates of hospitalisation amongst all groups.

Hospitalisation for all causes, all ages, by gender for July 2020 to June 2023, within Ngāi Tahu Takiwā

| Māori | Non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av. no. per year | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | Av. no. per year | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | ||

| Female | 11,926 | 20,769 (20,397, 21,142) | 100,317 | 18,553 (18,438, 18,668) | 1.12 (1.10, 1.14) |

| Male | 8,801 | 14,688 (14,381, 14,995) | 80,326 | 13,840 (13,744, 13,936) | 1.06 (1.04, 1.08) |

| Total | 20,762 | 17,663 (17,423, 17,903) | 180,951 | 16,129 (16,055, 16,204) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.11) |

Source: NMDS, Te Whatu Ora.

Notes: Age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

Internationally, Indigenous peoples consistently report a lack of engagement and connection when accessing hospital services, and it is the same in New Zealand. A recent New Zealand study (Komene et al, 2023) looked at the experiences of thirteen whānau and patients and identified that those who felt understood by their care teams (holistically, culturally and ethnically) felt more engaged, and they emphasised the need for effective, two-way, communication that recognised the importance of whānau in decision-making. This study also noted that Māori and whānau spoke about the structural racism they encountered in hospital services.

Preventable and avoidable hospitalisations

There are two ways data can help us look at hospitalisations that could be prevented:

- Potentially avoidable hospitalisations, which are those which could have been prevented by primary health care, public health, or social policy intervention, or

- Ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations, which are those which could have potentially been avoided through interventions in primary care.

When it comes to potentially avoidable hospitalisations, Māori had slightly higher rates of hospitalisation than non-Māori. For example, for people within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā aged 15 to 24 years old, Māori were 1.2 times more likely than non-Māori to be hospitalised for potentially avoidable causes between July 2022 and June 2023.

Potentially avoidable hospitalisations, aged 15 to 24 years, July 2022 to June 2023 within Ngāi Tahu Takiwā

| Māori | Non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | Number | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | ||

| Total | 697 | 3,300 (3,055, 3,545) | 3,201 | 2,813 (2,716, 2,910) | 1.17 (1.08, 1.27) |

Source: NMDS, Ministry of Health.

Note: Age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

For Ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations Māori again had higher rates of hospitalisation. For example, for people within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā aged 45 to 64 years, Māori aged 45 to 64 years had a rate of ambulatory sensitive hospitalisation that was 1.7 times that of non-Māori.

Ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations, aged 45 to 64 years, July 2022 to June 2023 within Ngāi Tahu Takiwā

| Māori | Non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | Number | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | ||

| Total | 856 | 3,912 (3,650, 4,174) | 6,075 | 2,303 (2,245, 2,361) | 1.70 (1.58, 1.82) |

Source: NMDS, Ministry of Health.

Note: Age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

Research looking at trauma admissions for Māori at Christchurch Hospital has shown that for both the Māori and total populations, the incidence rate of major trauma

in Canterbury is higher than rates in the North Island. However, the incidence rate for Māori was slightly higher than for the total Canterbury population (Kandelaki et al, 2021).

For more information on hospitalisations and mental health refer to [link to mental health and hospitalisations section below].

Long term conditions

A small group of long-term conditions are responsible for many of preventable deaths of Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā (outlined in the section on Potentially avoidable deaths above [insert link]). These include diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, and stroke and are driven by a range of risk factors including tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy diets.

This section looks at some key indicators connected to these long-term conditions. For more detailed information, please refer to Te Tauraki Māori Health Profile Volume Two.

Tobacco use

Around 26.7% of Māori aged 15 years and over in the Ngāi Tahi Takiwā were regular (daily) smokers, according to the 2018 Census. The rate was slightly higher for Māori women than for Māori men and overall Māori were about twice as likely to be regular smokers as non-Māori in the Takiwā. New Zealand Health Survey Data shows that between 2017 and 2022 11.9% of Māori in the Takiwā were vaping on a daily basis, with the rates in the former West Coast DHB region and the former South Canterbury DHB region being higher than other parts of the Takiwā.

Around 12.6% of rangatahi Māori in the Takiwā aged 15 to 19 years were regular smokers, according to the 2018 Census. Male rangatahi Māori had a slightly higher smoking rate than female rangatahi Māori. Again, rangatahi Māori were around twice as likely to be regular smokers as non-Māori rangatahi.

Cardiovascular disease

Between 2020 and 2023, Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were 1.5 times more likely than non-Māori to be hospitalised for circulatory system diseases (which includes hospitalisations from conditions such as rheumatic fever, high blood pressure, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and other forms of heart disease).

Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were more than twice as likely as non-Māori to be hospitalised for heart failure. The rate of hospitalisation was highest for Māori males.

This is consistent with the pattern of Māori health inequities across the country. For example, evidence shows Māori experience stroke at a younger age and are at greater risk than New Zealanders of European ethnicity. Not only have these inequities persisted for decades but there is some evidence suggesting the gap is widening. Research evidence emphasises the importance of approaches that support Māori-led solutions (Ranta et al, 2023).

Diabetes

Based on data held in the Virtual Diabetes Register, roughly 4,385 Māori (2,201 women and 2,184 men) aged 25 years or older in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā had diabetes in 2022 (an estimated 6.2% of Māori in the age group). After adjusting for differences in the population age structures, Māori in the Takiwā were 1.5 times more likely than non-Māori to have diabetes. Yet, Māori were also significantly less likely (0.9 times) than non-Māori with diabetes to be regularly receiving diabetes medicines. While not all people with diabetes require medication, those that do should take it regularly for optimum diabetes control. The presence of ethnic differences in medication receipt raises questions about the quality of care and access to appropriate treatment for Māori, especially when Māori with diabetes in the Takiwā have higher rates of preventable diabetes complications.

Diabetes prevalence, aged 25 years and over, 2022, within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā

| Sex | Māori | non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | (95% CI) | Number | % | (95% CI) | ||

| Female | 2,201 | 6.4 | (6.1, 6.7) | 21,133 | 3.7 | (3.7, 3.8) | 1.71 (1.63, 1.79) |

| Male | 2,184 | 6.0 | (5.7, 6.2) | 24,197 | 4.3 | (4.2, 4.4) | 1.39 (1.33, 1.46) |

| Total | 4,385 | 6.2 | (6.0, 6.4) | 45,330 | 4.0 | (4.0, 4.1) | 1.54 (1.49, 1.59) |

Source: Virtual Diabetes Register, Ministry of Health.

Notes: Percentages are age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

Respiratory disease

Between 2020 and 2023, asthma hospitalisations were highest for Māori children, with an average of 94 Māori children (aged 14 years and younger) per year in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā hospitalised for asthma, a rate 1.7 times higher than for non-Māori.

Māori in the Takiwā aged 45 years and older were also 2.4 times more likely than non-Māori to be hospitalised for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Māori also had higher rates of hospitalisation from bronchiectasis across the Takiwā than non-Māori (a rate of 9.3 per 100,000 people for Māori compared with 7.8 per 100,000 for non-Māori), although small numbers make it hard to draw conclusions for all regions. On average, there were 15 premature Māori deaths each year from respiratory disease within the Takiwā between 2014 and 2018.

Gout

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, and people with gout typically experience recurrent flare of severe joint inflammation which, if not properly treated, can lead to tophi, chronic arthritis, and joint damage.

Māori men in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were more likely to be affected by gout than any other population group with around 3,012 Māori males (or 7.5% of Māori males) aged 20 years or older affected in 2022. This data is based on those who were hospitalised with gout or prescribed gout medication and who are enrolled with a primary health organisation (PHO), so it may not capture everyone with gout in the Takiwā.

Gout prevalence, aged 20 years and over, 2022, in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā

| Sex | Māori | non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | (95% CI) | Number | % | (95% CI) | ||

| Female | 852 | 1.9 | (1.8, 2.0) | 7,966 | 0.9 | (0.9, 0.9) | 2.08 (1.92, 2.24) |

| Male | 3,012 | 7.5 | (7.2, 7.8) | 27,503 | 4.3 | (4.3, 4.4) | 1.73 (1.66, 1.80) |

| Total | 3,864 | 4.7 | (4.6, 4.9) | 35,469 | 2.6 | (2.6, 2.6) | 1.81 (1.75, 1.88) |

Source: NMDS, Pharmaceutical Collection, PHO enrolments, Mortality Collection, New Zealand Cancer Registry, Ministry of Health. Notes: Includes those enrolled with PHOs only. Percentages are age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

Gout is treated through long-term urate-lowering medications, such as allopurinol, but data shows that only 42.2% of Māori with gout in the Takiwā were receiving regular urate-lowering medication. This is roughly the same proportion as for non-Māori, but as Māori with gout have earlier onset and more severe disease, equitable care would require higher levels of medication prescribing (Health Quality and Safety Commission, 2024).

Cancer

Cancer is a leading cause of illness and death for Māori across the country, making up 25% of amenable mortality for Māori females and 10% for Māori males (Ministry of Health, 2010).

Broad health system actions that impact multiple cancers, such as improving access for Māori to prevention, timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment (regardless of income or place of residence), increased Māori control in cancer decision making and Māori-led services are crucial to improving Māori outcomes in the area (Gurney, Robson et al. 2020).

Cancer vaccines

Preventing the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, which causes virtually all cervical cancers, through HPV immunisation is an important contribution to reducing the incidence of cancer. HPV vaccine is part of the routine NZ National Immunisation Schedule to be given to all 12-year-olds. However, the rate of HPV vaccination is lower for Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā at 14 years of age (55.8% as at June 2023) than non-Māori (68.4% as at June 2023).

Cancer screening

Cancer screening is a way to find and treat cancer early, to support the best possible cancer outcomes for people. There are three national cancer screening programmes covering breast cancer, cervical cancer, and bowel cancer.

In 2023, Māori participation in all three cancer screening programmes within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā was lower than for non-Māori:

- For breast cancer screening 68.7% of eligible Māori (aged 45 to 69 years) have been screened in the previous two-year period, compared to 72.8% of non-Māori.

- For cervical cancer screening, 63.8% of eligible Māori (aged 25 to 69 years) were up-to-date within their cervical screening, compared to 73.8% of non-Māori.

- For bowel cancer screening, 60.2% of the eligible Māori population has been screened compared to 64.8% of non-Māori.

Cancer diagnoses

Within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā, the most common types of cancer diagnosed for Māori between 2016 and 2020 were lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colorectal (bowel) cancer. This is the same as the most common types of cancer diagnosed for Māori nationally. Notably, the rate of lung cancer in Māori was 2.92 times higher than for non-Māori in the Takiwā, with the rate being higher for Māori females (who were 3.26 times more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer than non-Māori).

Most common cancer registrations, by site, all ages, 2016 to 2020, Ngāi Tahu Takiwā

| Sex | Māori | non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av. no. per year | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | Av. no. per year | Age-standardised rate per 100,000 (95% CI) | ||

| Females | |||||

| All cancers | 144 | 215.2 (180.5, 254.9) | 2,410 | 189.4 (179.3, 199.9) | 1.14 (0.95, 1.36) |

| Breast | 42 | 63.7 (45.5, 86.9) | 648 | 60.7 (55.1, 66.7) | 1.05 (0.76, 1.45) |

| Lung | 26 | 35.0 (22.8, 52.0) | 205 | 10.7 (9.1, 12.9) | 3.26 (2.14, 4.95) |

| Colorectal | 12 | 18.5 (9.5, 32.9) | 369 | 22.8 (19.7, 26.4) | 0.81 (0.45, 1.47) |

| Uterus | 6 | 9.5 (3.3, 21.4) | 110 | 8.7 (6.9, 11.1) | 1.09 (0.46, 2.57) |

| Males | |||||

| All cancers | 154 | 216.9 (183.2, 255.4) | 2,890 | 202.3 (193.1, 212.0) | 1.07 (0.91, 1.27) |

| Prostate | 35 | 44.5 (30.9, 62.6) | 889 | 56.5 (52.6, 60.8) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.11) |

| Lung | 25 | 31.7 (20.4, 47.7) | 227 | 12.2 (10.4, 14.4) | 2.59 (1.69, 3.97) |

| Colorectal | 16 | 22.2 (12.5, 36.9) | 395 | 26.4 (23.2, 30.0) | 0.84 (0.50, 1.41) |

| Leukaemia | 8 | 14.8 (6.2, 29.3) | 99 | 9.4 (6.8, 12.7) | 1.58 (0.73, 3.42) |

| Total | |||||

| All cancers | 298 | 216.5 (192.0, 243.5) | 5,300 | 195.1 (188.2, 202.1) | 1.11 (0.98, 1.25) |

| Lung | 51 | 33.4 (24.8, 44.3) | 431 | 11.4 (10.2, 12.9) | 2.92 (2.17, 3.94) |

| Breast | 43 | 31.8 (22.8, 43.4) | 653 | 30.9 (28.1, 33.9) | 1.03 (0.75, 1.42) |

| Prostate | 35 | 22.7 (15.8, 32.0) | 889 | 27.6 (25.6, 29.7) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.16) |

| Colorectal | 29 | 20.4 (13.4, 29.8) | 764 | 24.5 (22.3, 27.0) | 0.83 (0.56, 1.23) |

Source: New Zealand Cancer Registry, Ministry of Health.

Notes: Colorectal includes colon, rectum and rectosigmoid junction. Age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

Cancer deaths

For Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā the most common causes of cancer deaths were lung cancer, colorectal (bowel) cancer, liver cancer and breast cancer. Māori were 1.3 times more likely than non-Māori to die from any type of cancer, including 2.4 times more likely to die from lung cancer and 3.6 times more likely to die from liver cancer.

Mental health and addictions

Mental health and substance use conditions are considerable contributors to overall health loss for Māori (Ministry of Health 2016). Māori are more likely to experience

psychological distress and mental health and substance use conditions than non-Māori, but evidence shows Māori experience poorer mental health care. This includes being less likely to receive medicines in line with need (Metcalf et al, 2018), and being more likely to be placed in seclusion (McLeod et al, 2017). People with mental health conditions are also more likely to experience discrimination, even within health care services, with Māori with mental health and substance use conditions were less likely than non-Māori with mental health and substance use conditions to report being treated with respect and listened to and were more likely to report experiencing unfair treatment (Cunningham et al, 2024).

Mental health outcomes are influenced by many of the determinants of health discussed in (the determinants of health section).

Prevalence of mental health problems

Between 2017 and 2022, 17.6% of Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā aged 15 years and older experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared to 11% of non-Māori. The rate was even higher for Māori women, 22.2% of whom experienced high or very high psychological distress. Measuring prevalence of mental health problems can be difficult and for more detailed technical notes please refer to Te Tauraki Māori Health Profile – Volume Two.

| Sex | Māori | non-Māori | Māori/non-Māori rate ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | ||

| Female | 22.2 | (15.0, 30.9) | 12.3 | (10.4, 14.4) | 1.92 (1.36, 2.72) |

| Male | 13.1 | (8.6, 18.9) | 9.7 | (7.8, 12.0) | 1.44 (1.01, 2.05) |

| Total | 17.6 | (13.6, 22.1) | 11 | (9.5, 12.6) | 1.70 (1.35, 2.14) |

Source: New Zealand Health Survey, Ministry of Health.

Notes: Psychological distress means having high or very high levels of psychological distress on the K10 scale, that is, a score of 12 or more. Percentages are age-standardised to the 2001 Māori Census Population.

Use of alcohol and drugs

Between 2017 and 2022, 38.5% of Māori aged 15 years and older within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were found to have a hazardous drinking pattern, in the previous year, according to data collected through the New Zealand Health Survey. This is 1.6 times higher than the rate of hazardous drinking amongst non-Māori in the Takiwā.

Episodic, or ‘binge drinking’, is also associated with a higher risk of experiencing alcohol related harm and of developing chronic health conditions. As with hazardous drinking, Māori within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were more likely to binge drink at least monthly than non-Māori (36.4% for Māori compared to 26.4% for non-Māori). The rate of heavy episodic drinking was highest for Māori males (45.8%).

There is less data available on the hazardous use of drugs other than alcohol. There is, however, some data on cannabis use. Between 2017 and 202, 34% of Māori aged 15 years and older in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā reported they had used cannabis in the past year, which was nearly twice the rate of non-Māori.

Mental health, substance use, and hospitalisations

Between 2020 and 2023 Māori within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were 1.8 times more likely than non-Māori to be hospitalised for any type of mental health or substance use disorder. The highest hospitalisation rates for Māori compared to non-Māori are for schizophrenia (3.4 times higher for Māori), and substance/alcohol use (2 times higher for Māori). As with much of the. Mental health data these should be interpreted with caution as data tends to be more incomplete for mental health conditions than for other health conditions – so the data may be underestimated. For more discussion on the quality of the mental health data, please see Te Tauraki Māori Health Profile, volume two.

Between 2020 and 2023, Māori aged 15 to 44 years in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā were 1.5 times more likely to be hospitalised for intentional self-harm than non-Māori at the same age. The rate is higher for Māori women than it is for any other group.

Māori are less likely to be dispensed medication for depression

One measure of mental health care is the prescription of medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly prescribed antidepressant medication. Despite evidence suggesting Māori have a higher prevalence of depression, and likely higher need for medication, Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā aged 15 years and older were less likely to have regular SSRI medication than non-Māori. Medication is not the only treatment for depression, but this large ethnic difference in the rate of receiving antidepressant medication raises questions about access to and receipt of appropriate depression treatment for Māori in the Takiwā.

Determinants of health

Determinants of health are the things outside of the health sector that contribute to our overall health and wellbeing. When things are going well, the determinants of health can help us to stay healthy and prevent us from getting ill.

Data and statistics for the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā highlight the unfair and unjust differences in access many Whānau Māori have to determinants of health, including:

- Relative deprivation (using the NZDep18 tool)

- Impacts of the costs of living

- Access to transport and telecommunications

- Rurality

- Education and employment

- Housing.

Much of the information in this section is drawn from Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume One. (December 2023), and this document also has additional data – sometimes broken down by former-DHB region.

Relative deprivation

The NZ Deprivation Index 2018 (NZDep18) is a tool used to understand socio-economic status of communities across the country. The NZDep18 is an aggregate measure, providing information about the wider socio-economic environment in which a person lives, rather than information about their individual socio-economic status. There are ten deciles, with decile 1 being relatively least deprived and decile 10 being relatively most deprived.

Findings from Te Kupenga and the 2018 census show that there are different patterns of socio-economic deprivation across regions within our Takiwā.

- In the former West Coast DHB region, 27% of Māori lived in the two most deprived deciles (deciles 9 and 10). In comparison, 24% of non-Māori in the former West Coast DHB region lived in the two most deprived deciles. Similarly, only 5% of Māori in the region lived in the two least deprived deciles (deciles 1 and 2), compared with 7% of non-Māori

- In the former Canterbury DHB region, 21% of Māori lived in the two most deprived deciles, compared with 10% of non-Māori. Eighteen percent of Māori lived in the two least deprived deciles, compared with 29% of non-Māori

- In the former South Canterbury DHB region, 17% of Māori lived in the two most deprived deciles, compared with 12% of non-Māori. Eight percent of Māori lived in the two least deprived deciles, compared with 14% of non-Māori

- In the former Southern DHB region, 24% of Māori lived in the two least deprived deciles, compared with 13% of non-Māori. Sixteen percent of Māori lived in the two least deprived deciles, compared with 24% of non-Māori

While the former West Coast DHB region is the most deprived overall in our Takiwā, 61% of Māori in Te Tauraki living in the most deprived decile live in the former Canterbury DHB region.

Costs of living

Māori in Te Tauraki over 20 years of age are significantly more likely than non-Māori to receive an income of $20,000 or less:

- 37.4% of Māori in the former West Coast DHB region are living on an income of $20,000 or less (compared with 30.7% of non-Māori)

- 31.2% of Māori in the former Canterbury DHB region are living on an income of $20,000 or less (compared with 26.2% of non-Māori)

- 31.1% of Māori in the former South Canterbury DHB region are living on an income of $20,000 or less (compared with 25.7% of non-Māori)

- 31.2% of Māori in the former Southern DHB region are living on an income of $20,000 or less (compared with 27.8 of non-Māori)

In 2018, because of cost:

- 7.2% of Māori aged over 15 years in our Takiwā reported often postponing or putting off a doctor’s visit

- 4.4% of Māori aged over 15 years in our Takiwā often went without fresh fruit and vegetables

- 7.8% of Māori aged over 15 years in our Takiwā often put up with feeling cold

Access to transport and telecommunications

Whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā are 1.8 times more likely than non-Māori to be without access to a motor vehicle. This equates to 5.1% of Māori (4,110 people) living in our Takiwā with no access to a motor vehicle compared to 2.8% of non-Māori in 2018.

Travel has also been raised by whānau Māori in community engagement as a barrier to accessing health care, particularly in areas like the West Coast:

“…consider the needs of all whānau when a whānau member needs to travel out of region for specialist health care – whānau needs to be supported to be with them.”

– Takiwā Poutini. Community engagement, 2023

Whānau Māori in Te Tauraki are 1.4 times more likely than non-Māori to have no access to telecommunications (a functional cellphone, telephone, or the Internet).

Research looking into Māori experiences of social housing across Ōtautahi (Christchurch) found transport enables connection and supports wellbeing for whānau Māori. The mode of transport whānau Māori use depends on things like cost, accessibility, and access to technology. The research also finds that improving transport access for whānau Māori n social housing requires transport solutions to be designed in partnership with Māori. (Russell et al, 2024)

Rurality

People living in rural areas often have poorer access to health services than those living in urban areas. Although around 73% of Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā live in urban areas, this varies by region.

- In the former West Coast DHB region, 100% of the population live in areas classed as rural

- In the former Canterbury DHB region, around 13% of Māori live in rural areas

- In the former South Canterbury DHB region, around 23% of Māori live in rural areas

- In the former Southern DHB region, around 39% of Māori live in rural areas.

Education and employment

In 2018, 63.2% of Māori aged 20 years and over in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā had achieved Level 2 certificate or higher. A level 2 certificate qualifies individuals with introductory knowledge and skills for a field(s)/areas of work or study.

When it comes to work and employment, in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā in 2018:

- Just over half of Māori aged 15 years and over were employed full time (51.9%)

- Around 6.5% of Māori were unemployed, which is 1.6 times the rate of non-Māori unemployment

- While the figures were similar across all former DHB regions in the Takiwā, unemployment was highest for Māori in the former Canterbury DHB region.

The main employers for Māori in the Takiwā vary by gender. For Māori females, the health care and social assistance industry is the largest employer, whereas for Māori males construction is the leading industry (21.8% of Māori males).

The following table looks at the leading industries in which Māori were employed in the Takiwā in 2018, by gender.

| ANZSIC Industry | Māori | non-Māori | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Rank | Number | % | Rank | |

| Females | ||||||

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 2,775 | 13.6% | 1 | 37,452 | 16.8% | 1 |

| Retail Trade | 2,508 | 12.3% | 2 | 25,815 | 11.6% | 3 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 2,469 | 12.1% | 3 | 21,096 | 9.5% | 4 |

| Education and Training | 2,223 | 10.9% | 4 | 27,324 | 12.2% | 2 |

| Manufacturing | 1,668 | 8.2% | 5 | 14,037 | 6.3% | 6 |

| Males | ||||||

| Construction | 4,944 | 21.8% | 1 | 43,416 | 17.1% | 1 |

| Manufacturing | 3,651 | 16.1% | 2 | 34,509 | 13.6% | 2 |

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 2,085 | 9.2% | 3 | 25,515 | 10.1% | 3 |

| Transport, Postal and Warehousing | 1,527 | 6.7% | 4 | 15,000 | 5.9% | 6 |

| Retail Trade | 1,482 | 6.5% | 5 | 19,320 | 7.6% | 5 |

Source: 2018 Census, Statistics New Zealand.

Note: Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC).

Leading industries in which Māori were employed, Te Tauraki, 2018

Unpaid work is very common for Māori in the Takiwā and is slightly more common than for non-Māori. For Māori aged 15 years or over, 89.1% said they performed unpaid work in 2018, and 9.2% were looking after a disabled or ill household member.

Housing

The Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume One. (December 2023) provides useful data on housing and whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā.

Whānau Māori aged 20-years and over in our Takiwā are less likely than non-Māori to own their own home, with 59.2% of Māori aged 20 years or over living in a home they did not own, partially own, or hold in a family trust (compared with 49.3% of non-Māori).

Whānau Māori were more likely to live in an overcrowded home in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā than non-Māori. Around 11% of whānau Māori live in homes requiring at least one more bedroom compared with around 89% for non-Māori.

Whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā are more likely to live in homes with quality issues. In 2018:

- Around 31% of whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā (or around 22,638 people) lived in a home that was sometimes or always damp and were 1.5 times more likely than non-Māori to live in a damp home

- Around 22% of whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā (or around 16,122 people) lived in a house with mould and were 1.6 times more likely to live in a mouldy home.

- Whānau Māori in Te Tauraki were slightly more likely than non-Māori to live in homes without any source of heating (0.7% of Māori, compared with 0.6% of non-Māori).

On the West Coast, the Takiwā Poutini summary of community voice and experiences identified that Iwi-led kaumatua housing and emergency housing systems were both seen as important to whānau Māori, as was access to healthy homes.

Māori experiences of racism

Racism attacks rangatiratanga and has the potential to interrupt how people live their lives as individuals and as whānau, hapū, and iwi and it can also compromises the ability of whānau pass on Māori ways of knowing and being to future generations.

A 2019 survey of over 500 participants, including 100 attendees at the 2019 Ngāi Tahu Hui-a-Iwi, found that the vast majority of Māori (93%) felt racism had an impact on them on a daily basis and even more (96%) said that racism was a problem for their wider whānau at least to some extent. Māori felt most comfortable on marae, at home, or at iwi events, but felt less comfortable identifying as Māori in education and workplace settings. (Smith et al, 2021). Racism and health research in New Zealand consistently finds that self-reported racial discrimination is associated with a range of poorer health outcomes and reduced access to and quality of healthcare (Talamaivao et al, 2020).

Health data and statistics sources

Health data and statistics are one dimension of ‘whānau Māori voice’. Data represents Māori stories and Māori lived experience based on the information routinely collected by the health system and through national surveys (such as the census and the New Zealand Health Survey).

Data and statistics also help us see inequities in health outcomes for Māori compared with other groups, which reinforces the collection of data by health agencies part of the system’s broader commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

The health data we use primarily comes from the following reports and sources:

Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume One. (December 2023)

Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume One. (December 2023)

This report includes key demographic information about whānau Māori in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā and looks at:

- Mauri ora (overall health status),

- Whānau ora (healthy families) and

- Wai ora (healthy environments) indicators.

A second volume with additional indicators focused on Te Aka Whai Ora-identified health priority areas (e.g. cancer, long-term conditions, first 1,000 days and mental health) is under development.

Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume Two. (May 2023)

Iwi-Māori Partnership Board Health Profile: Te Tauraki. Volume Two. (May 2023)

This report contains health service utilisation and outcomes measures with a focus on four health priority areas:

- The first 1000 days

- Cancer

- Long-term conditions

- Mental health.

Ministry of Health – Māori data and statistics

The Ministry of Health’s statistical reports on Māori health are available on its website. This includes Tatau Kahukura, which presents key indicators on the socio-economic determinants of health, risk and protective factors for health, health status, and health service use at a national (rather than regional) level. It is not specifically focused on the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā.

Ministry of Health – Life Expectancy in Aotearoa, New Zealand 2001 - 2022

“The following report, Life Expectancy in Aotearoa New Zealand: 2001–2022, analyses trends and disparities in life expectancy across socioeconomic, geographic, gender, and ethnic lines. It highlights gaps, particularly for Māori and Pacific peoples, and uses decomposition analysis to explore avoidable mortality. The findings aim to inform policies for greater health equity”

Tatauranga Aotearoa | Status NZ - Te Kupenga Survey

https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/te-kupenga-2018-final-english

Te Kupenga is a survey of Māori wellbeing. The survey includes almost 8,500 adults (aged 15 years and over) of Māori ethnicity and/or descent, and gives an overall picture of the social, cultural, and economic wellbeing of Māori people in Aotearoa. This includes data tables that breaks down the survey responses by geographic region.

Te most recent Te Kupenga data releases (from 2018) are available here.

Te Whatu Ora | Health New Zealand, health status report (2024)

https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/publications/health-status-report/

This health status report outlines demographic information, prevalence and incidence data related to health status, and key preventable risk factors. It also includes some information on rurality and different geographic communities. It is not specifically focused on Māori health or the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā.

A note about ethnicity data

Our understanding of inequity, health system performance, and Māori health outcomes rely on high quality data collection, storage, use, and analysis. Ethnicity data protocols have been in place across the health system for nearly 20 years. Despite this, several studies show that there are serious ethnicity data quality issues, and that Māori are systematically undercounted. For example, in linked analysis Māori were under-counted on the National Health Index (NHI) by 16%. Under-representation in data and under-counting are more pronounced for Māori men. (Harris et al, 2022).

A note about regions within the Takiwā

The Ngāi Tahu Takiwā is set according to Iwi boundaries and are acknowledged by the government and recognized in legislation in the Ngāi Tahu settlement legislation (https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/private/1996/0001/latest/whole.html#DLM117230)

This means at times we have had to use data broken down by former DHB boundaries as a proxy for what is happening for whānau Māori in our Takiwā. Sometimes, this is tidy. For example the former West Coast, Southern, and South Canterbury district health boards (DHBs) are all entirely within the Takiwā. The Takiwā also includes virtually all the former Canterbury DHB, however, it only includes some parts of the former Nelson Marlborough DHB. Over time, we expect data to be analysed by health agencies according to the Takiwā geographic boundaries, to give us a more accurate picture of whānau Māori voice.

Local Reports

This section outlines reports from Iwi, Papatipu Rūnaka, and groups local to the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā that provide insights into whānau Māori voice.

Ngāi Tahu Whānau Survey (2018)

This survey was conducted by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Research first to gain a better understanding of Ngāi Tahu whānau members. It includes insights into whānau wellbeing and access to health services and information.

He Tohu Ora

This outcomes framework was developed between Ngāi Tahu and Te Putahitanga o Te Waipounamu whānau ora commissioning agency. Three different data sources are used in He Tohu Ora: Te Kupenga (2013 and 2018), a survey of Māori wellbeing across New Zealand conducted by Statistics New Zealand; the Census of Population and Dwellings (2018); and the Canterbury Wellbeing Survey (2012–2022), which is produced by Te Whatu Ora Waitaha – formerly the Canterbury District Health Board.

Socio-economic impact and regional multipliers analysis for the Te Kāika expansion (2023)

This report, produced by Te Kāika (a Māori low-cost healthcare and social services provider in Dunedin), this report outlines the issues that whānau Māori in the former-Southern DHB region face and the impact of inequities on Māori health oucomes in the area.

Takiwā Poutini Community and Whānau Māori Voice (2023)

The protype locality of Takiwā Poutini produced a summary of existing community voice and experiences in 2023 as part of their function to produce a locality plan. This report identified priority areas including:

- Workforce, cultural competency, and ongoing training

- A whānau ora approach

- Eliminating racism, discrimination, and bias

- More connection across sectors (including housing, transport, and kai).

A link to the summary is available here.

He Waka Tapu Annual Report (2021)

In 2021, He Waka Tapu (a Kaupapa Māori organisation serving Ōtautahi (Christchurch), Hakatere (Ashburton), and the Chatham Islands, commissioned a survey of its service user experiences. Insights from this survey highlight the importance of Māori-led services in the Takiwā.

Christchurch Clinical Network report (2022)

In 2022, the Christchurch Clinical Network team reviewed feedback from health system staff and consumers and identified several concerns and barriers to access for whānau (including embarrassment, costs, and lack of cultural safety). The report makes recommendations for the health system including simplifying access to services and ensuring more options for whānau.

TIPU MAHI - South Island Māori Health Workforce Development

TIPU MAHI is a project, set up to address Māori health inequities by specifically focusing on growing and supporting the Te Waipounamu (South Island) Indigenous Māori health workforce.

Canterbury Wellbeing Survey (2019)

Prepared for the former-Canterbury DHB, this survey (which is for the total population, but oversamples Māori in order to get an adequate sample size for robust statistical analysis) has findings on areas including disability and how safe people feel in their city or town centre.

Published Literature

University of Otago

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (and its predecessor, the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board) has a strong relationship with the University of Otago. In 1996, this relationship led to the creation of Te Roopū Rakahau Hauora Māori o Kāi Tahu (Ngāi Tahu Māori Health Research Unit), which is still operating today.

For more information on Te Roopū Rakahau Hauora Māori o Kāi Tahu and a list of their publications visit: https://www.otago.ac.nz/maori-health-research/publications

You can find out more about Māori health research in the Division of Health Sciences, University of Otago here: https://www.otago.ac.nz/healthsciences/research/maori

The University of Otago also has two other units specialising in Māori health and Māori health research:

Māori Indigenous Health Innovation (MIHI) at University of Otago, Ōtautahi

Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare at University of Otago, Whanganui-ā-Tara

Suggested reading

There is a wealth of Kaupapa Māori Research and health research relevant to whānau Māori. This section provides some suggested reading, as a starting point for those wanting to know about Māori health needs and aspirations.

Published articles mentioned in our whānau Māori voice summary

Cunningham R, Imlach F, Haitana T, et al. Experiences of physical healthcare services in Māori and non-Māori with mental health and substance use conditions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2024;58(7):591-602. doi:10.1177/00048674241238958. Available here.

Gurney, J. K., Robson, B., Koea, J., Scott, N., Stanley, J., & Sarfati, D. (2020). The most commonly diagnosed and most common causes of cancer death for Māori New Zealanders. NZ Med J, 133(1521), 77-96. Available here.

Ingham TR, Jones B, Perry M, King PT, Baker G, Hickey H, Pouwhare R, Nikora LW. The Multidimensional Impacts of Inequities for Tāngata Whaikaha Māori (Indigenous Māori with Lived Experience of Disability) in Aotearoa, New Zealand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013558

Kandelaki, T., Evans, M., Beard, A., Wakeman, A. (2021) Exploring admissions for Māori presenting with major trauma at Christchurch Hospital, NZ Med J. Vol 134 No 1530, available here.

Komene, E., Pene, B., Gerard, D., Parr, J., Aspinall, C., & Wilson, D. (2024). Whakawhanaungatanga—Building trust and connections: A qualitative study indigenous Māori patients and whānau (extended family network) hospital experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 80, 1545–1558. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15912

Lawrie FA, Mitchell YA, Barrett-Young A, Clifford AE. Birth by emergency caesarean delivery: Perspectives of Wāhine Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Health Psychology. 2024;0(0), available here.

Metcalfe, S., Beyene, K., Urlich, J., Jones, R., Proffitt, C., Harrison, J., & Andrews, A. (2018). Te Wero tonu—the challenge continues: Māori access to medicines 2006/07–2012/13 update. NZ Med J, Vol 131 No 1485. Available here.

McLeod, M., King, P., Stanley, J., Lacey, C., & Cunningham, R. (2017). Ethnic disparities in the use of seclusion for adult psychiatric inpatients in New Zealand. NZ Med J, 130(1454), 30. Available here.

Paine, S. J., Walker, R., Lee, A., Loring, B., & Signal, T. L. (2023). Associations between maternal stressful life events and child health outcomes in indigenous and non-indigenous groups in New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2023.2292262

Ranta, A., Jones, B., Harwood, M., (2023) Stroke among Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand and solutions to address persistent inequities Sec. Population Health and Risk Factors of Stroke Volume 2 – 2023 https://doi.org/10.3389/fstro.2023.1248351

Russell, E., McKerchar, C., Berghan, J., Curl, A., & Fitt, H. (2024). Considering the importance of transport to the wellbeing of Māori social housing residents. Journal of Transport & Health, 36, 101809. Available here.

Smith, C., Tinirau, R., Rattray-Te Mana, H., Tawaroa, M., Moewaka Barnes, H., Cormack, D., and Fitzgerald, E. (2019) Whakatika: Survey of Māori Experiences of Racism. Te Atawhai o Te Ao, Whanganui. Available here.

Talamaivao, N., Harris, R., Cormack, D., Paine, S. J., & King, P. (2020). Racism and health in Aotearoa New Zealand: a systematic review of quantitative studies. The New Zealand medical journal, 133(1521), 55–68. Available here.

Te Huia (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga), B., Brightwell (Ngāti Kahungunu, T., Cram (Ngāti Pāhauwera), F., & Tipene-Leach (Ngāti Kahungunu), D. (2023). Te Whare Pora a Hine-te-iwaiwa: weaving tradition into the lives of pregnant Māori women, new mothers and babies. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 19(4), 750-761. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801231197932

For a list of references we identified in a database search in early 2024, click here.